Identity Resilience and digital identity – key defences against cyber threats

23 August 2023

23 August 2023

Widespread collection and use of identity information such as passports and driver's licences in day to day business represents a systemic ecosystem risk that makes those holding identity information attractive to cyber attackers and fraudsters.

Organisations from the largest corporates and government bodies to small business need to collect identity information, often to comply with law.

Commonwealth, State and Territory governments have agreed a National Strategy for Identity Resilience, recognising the critical role that resilient identity and the adoption of digital identity plays in building Australia's vision of being the most cyber secure nation in the world by 2030.

Identity resilience, enabled by interoperable and portable digital identity, aims to provide more secure, robust, and trustworthy systems to prove we are who we say we are by making identity information harder to steal, harder to abuse, and easier to recover if compromised.

You can read more about the strategy and the push for new legislation in our recent publication Australian digital identity gains traction.

Identity crime is a significant cause of direct harm to the Australian economy in its own right – estimated to have cost $3.1 billion in 2018-19.

Stolen identity information can be a valuable commodity – used for identity fraud, or sold for others to use. According to Australian Bureau of Statistics research, stolen personal information is generally used to obtain money from bank accounts, superannuation, investments or shares (56%), as well as for other purposes, such as to open new phone and utility accounts (16%) or apply for loans or credit (7.9%).

Identity crime is a recognised key enabler of serious organised crime (estimated to cost the economy over $60 billion in 2020-21) as well as terrorism.

Identity crime be an enabler of further criminal activity (eg stolen identity information can set up fraudulent accounts, that can in turn be used for money laundering, or as further fraudulent proof of identity). Identity crime can also result from, or be the motivation to commit, cyber crime (eg a cyber attack to steal identity information).

Most importantly for organisations that need to manage identity information, the threat or possibility of identity crime is a key lever applied by ransom threat actors.

Identity crime causes significant emotional, psychological and financial harm. But this is only part of the picture. The threat that stolen information will be released or used for identity crime is powerful leverage which is applied by threat actors to extort ransom payments.

The Australian Government does not condone payment of ransoms, and consulted earlier this year on whether to ban ransom payments (as part of the 2023-2030 Australian Cyber Security Strategy).

Large organisations are already demonstrating they will not pay ransoms – focusing instead on supporting their customers through the consequences of a data breach.

But these incidents remain extremely costly and disruptive for targeted organisations, for the individual victims, and for the broader Australian community.

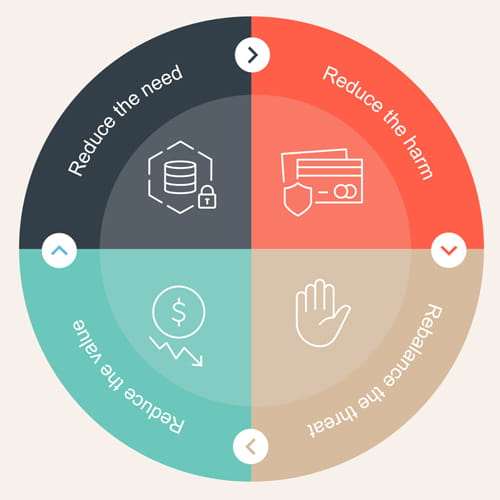

A resilient digital identity ecosystem reduces the harm flowing from a data breach – stolen credentials are harder to use for identity crime, and can be more easily re-issued or remediated (if required). Reducing a threat actor's ability to cause harm reduces the incentive to pay a ransom, which in turn should make an organisation less attractive for cyber attacks.

The rollout of digital identity, and its adoption by business, government and consumers will take time.

Business and government can take steps now:

You can read more about understanding your organisation's data and 4 key steps to addressing data risks.

Sensible and targeted data retention reforms are also on the regulatory agenda.

Regulatory requirements to authenticate or collect identity information can present a key challenge to implementing data minimisation techniques to combat cyber crime and identity theft.

Data retention and destruction obligations are diverse and overlapping, and are driven by different policy objectives. They are challenging to understand – and are often misunderstood. The result is that Australian organisations often retain data for longer than necessary.

The benefits of retaining information must now be balanced against the risks of retaining it – and the costs of keeping it secure.

One particular challenge for government bodies comes from regulations that may require them to retain sensitive information (including identity information) beyond its useful operational life. For example, the Archives Act 1983 (Cth) requires retention of personal information for in excess of 100 years in some cases.

The Privacy Act Review Report recommended that the Commonwealth Government review all data retention obligations for personal information to make sure that policy objectives are balanced against cyber security risks. Commonwealth, State and Territory Governments have committed as part of the new National Strategy for Identity Resilience to supporting business and government agencies to collect and retain less personal information where appropriate (balanced against legitimate law enforcement and regulatory needs for retention).

Private and public sector bodies with lived experience of data retention challenges and risks can help regulators and lawmakers strike the right balance. This will be an ongoing process – there will no doubt be some "easy wins", but more far-reaching reforms may need to move in lockstep with digital identity and identity resilience developments.

Holding identity information increases the already significant regulatory burden for the targets of cyber attacks.

Knowing whether a cyber incident involves identity information is essential to effectively protecting customers and complying with data breach notification obligations. This can be easier said than done unless you have a strong data governance framework and incident response plan.

When cyber incidents occur, organisations holding identity information are far more likely to be required to notify the privacy regulator and impacted individuals under the Australian Privacy Act Notifiable Data Breaches scheme.

Australia's privacy regulator has made it clear that:

This can mean an organisation holding identity information alongside other data can be required to give data breach notices for an attack that aims to disrupt the organisation, but not steal data (like a ransomware attack). Similarly, infiltration by a surveillance-based threat actor (such as Volt Typhoon) might trigger notification obligations even where the attacker has no obvious interest in stealing identity information.

If identity information has been compromised, customers may need to take steps to protect their identities and prevent fraud – the exact steps may depend on the identity information that has been compromised, and may mean talking to different government bodies. The National Strategy for Identity Resilience calls for "no wrong doors" for identity remediation – so individuals can talk to a single department – but this is a long-term initiative not expected for 3-5 years.

Reform proposals under consideration as part of Australia's overhaul of privacy laws will place additional pressure on organisations holding identity information. Proposed cyber security reforms include:

The new National Strategy for Identity Resilience calls for clear accountability and liability for the costs of remediating compromised identity credentials, with solutions that minimise harm to individuals – further increasing the potential costs associated with holding identity information.

Authors: Rebecca Cope, Partner; Mathew Baldwin, Partner; Bikram Choudhury, Director, Risk Advisory; and Andrew Hilton, Expertise Counsel

This publication is a joint publication from Ashurst Australia and Ashurst Risk Advisory Pty Ltd, which are part of the Ashurst Group.

The Ashurst Group comprises Ashurst LLP, Ashurst Australia and their respective affiliates (including independent local partnerships, companies or other entities) which are authorised to use the name "Ashurst" or describe themselves as being affiliated with Ashurst. Some members of the Ashurst Group are limited liability entities.

Ashurst Australia (ABN 75 304 286 095) is a general partnership constituted under the laws of the Australian Capital Territory.

Ashurst Risk Advisory Pty Ltd is a proprietary company registered in Australia and trading under ABN 74 996 309 133.

The services provided by Ashurst Risk Advisory Pty Ltd do not constitute legal services or legal advice, and are not provided by Australian legal practitioners in that capacity. The laws and regulations which govern the provision of legal services in the relevant jurisdiction do not apply to the provision of non-legal services.

For more information about the Ashurst Group, which Ashurst Group entity operates in a particular country and the services offered, please visit www.ashurst.com.

The information provided is not intended to be a comprehensive review of all developments in the law and practice, or to cover all aspects of those referred to.

Readers should take legal advice before applying it to specific issues or transactions.