London as a European restructuring forum reigns supreme

28 April 2023

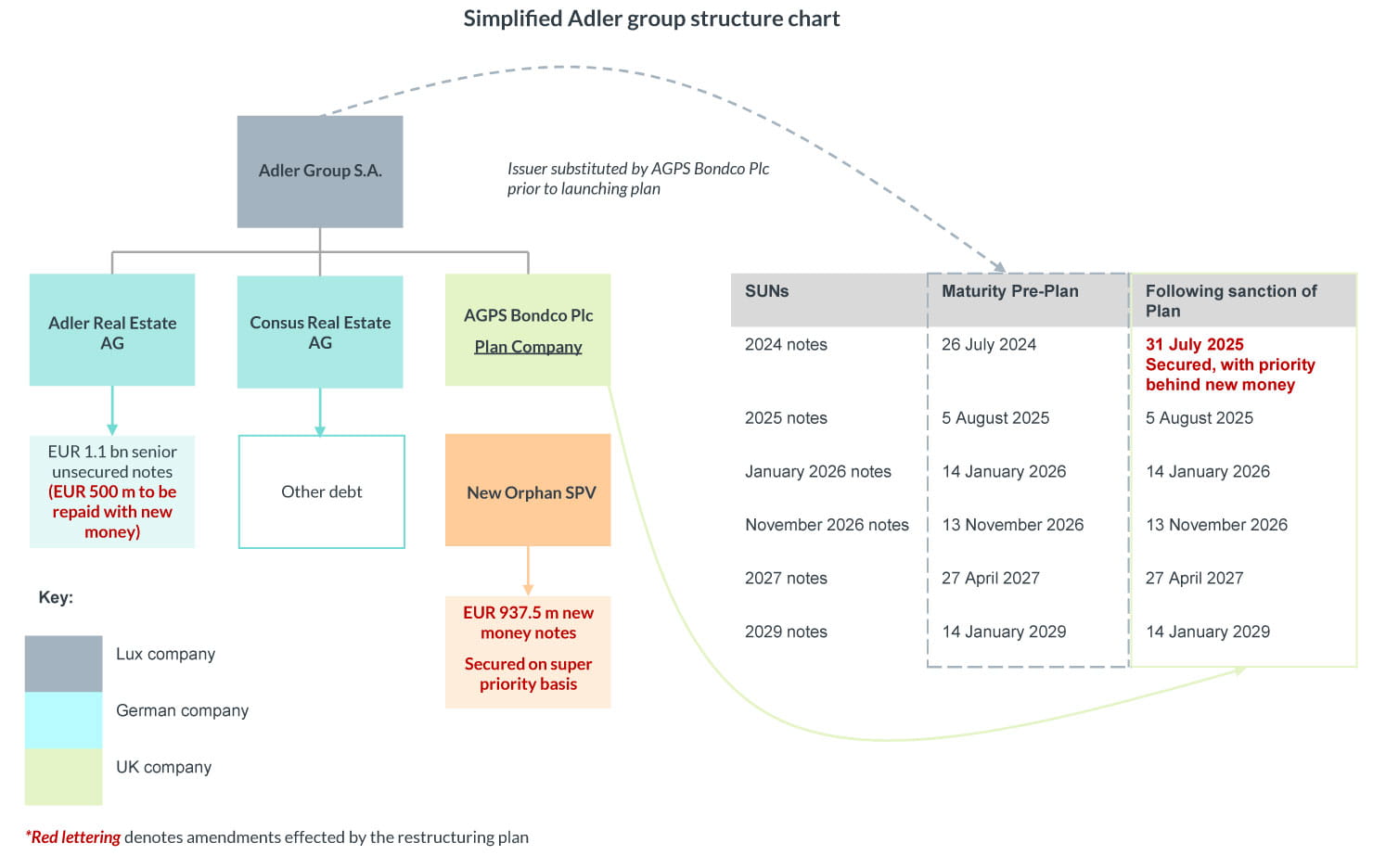

Having failed to get its restructuring solution through in its home jurisdiction, beleaguered German real estate group, Adler, turned to London. After substituting a UK plc as issuer of six series of notes in order to propose an English restructuring plan, and in the face of fierce opposition from an ad hoc committee of 2029 noteholders (AHG), the group successfully forced the plan through just in time.

The restructuring plan is still a very new tool, and this case provides important insight into how it works, including importantly how judges will approach a highly contested valuation dispute.

Did CIGA open the door for UK valuation disputes?When the Corporate Governance and Insolvency Act (CIGA) introduced the restructuring plan into our toolkit in June 2020, it was suggested that the new Part 26A so-called "super scheme" could give rise to protracted debtor/creditor valuation disputes, on account of its voting mechanism and ability to cram down whole dissenting classes. Until Adler came along, however, the English court was yet to see a full-blown valuation dispute. Virgin Active was the first restructuring plan in which it seemed possible that dissenting creditors might challenge the plan company's valuation evidence. Whilst dissenting classes of landlord creditors criticised the plan company's valuation evidence in that case, they declined to provide their own competing evidence for analysis. Snowden J took this opportunity to observe that it was important that "the potential utility of Part 26A is not undermined by lengthy valuation disputes" and it would be "most unfortunate if Part 26A plans were to become the subject of frequent interlocutory disputes". In Smile (No. 2), a senior lender did provide alternative valuation evidence in an effort to establish that it was not out of the money; but it did not formally oppose the plan in court, leading Snowden LJ to direct opposing creditors to "stop shouting from the spectators' seats and step up to the plate". Zacaroli J reiterated this message in Houst - the third restructuring plan which had potential to give rise to a valuation dispute – when HMRC chose not to provide alternative valuation evidence in spite of voting against the proposed plan. By contrast, US Chapter 11 proceedings (from which the cross-class cram down concept is borrowed) are renowned for giving rise to lengthy and costly valuation disputes in the bankruptcy courts. So common are valuation disputes in US Chapter 11 proceedings that it is a distinguishing factor to be taken into account if deciding whether to carry out a US- or UK-based restructuring. The market therefore watched with interest as Adler's restructuring plan was launched earlier this year. Following a failed consent solicitation process to amend the terms of certain of its senior unsecured notes (launched in accordance with German law in late 2022) in which a group of 2029 noteholders voted against the group's proposed amendments, it was clear that this restructuring might give rise to a larger scale valuation dispute in the English court. |

Adler is a German property group which owns a large number of rental properties and its portfolio is estimated to be worth around EUR 8 billion. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the invasion of Ukraine, a downturn in the property market and an adverse short seller report published in October 2021, the group is facing a liquidity crisis. As a result (and following its failed consent solicitation process), the group proposed a UK restructuring plan with six classes of creditors, being the holders of six series of senior unsecured notes (SUNs) due 2024, 2025, January 2026, November 2026, 2027 and 2029.

In brief, under the plan Adler proposed to (see diagram below):

The relevant alternative to the plan was a formal insolvency of the Group, which was accepted by both the AHG and the court.

The plan was approved by five out of six classes of creditors. As expected, the plan was not approved by the requisite majority of the 2029 noteholders, with 37.72% voting against.

Mr Justice Leech sanctioned the plan on 12 April. An application to appeal the decision was heard by Leech J in a subsequent hearing on 25 April in which permission to appeal was denied, which started the clock on a 21-day window in which the AHG may apply to the Court of Appeal to appeal the refusal.

The written sanction hearing judgment is lengthy (running to 164 pages in total) and covers various issues, which are briefly summarised in the table below. Our key takeaways from the judgment are as follows:

Olga Galazoula, Global Practice Head of Restructuring and Special Situations, says:

"This is the first major use of a restructuring plan post-Brexit by a substantial German group and proves that despite Brexit, London is still the go-to place for European restructurings. Domestically, it is one of the first plan cases involving a serious valuation dispute and increases our journey of understanding how the restructuring plan will respond in those scenarios."

| Issues considered at the sanction hearing | |

|---|---|

| Issue | Decision |

| Did the proposed restructuring contravene the pari passu principle? | No. The plan preserves the existing maturities of the SUNs (save for the 2024 notes) and noteholders will be paid in full. |

| Were the conditions for cross-class cram down satisfied and should the court exercise its discretion to cross-class cram? This required a detailed analysis of whether the 2029 noteholders (as the dissenting class) would be "any worse off" under the plan than they would be in the event of the relevant alternative, for which the court considered the valuation evidence provided by the plan company and the AHG. | Yes. The court preferred the plan company's valuation evidence and accepted that the 2029 noteholders would be paid in full if the plan was sanctioned and would receive 63% of their principal in the relevant alternative. |

| Was the substitution of the issuer (to avail itself of the English court's jurisdiction) valid? | Yes. The issuer substitution was valid and effective and the English court therefore had jurisdiction to sanction the plan. Note that the AHG are also litigating the validity of the issuer substitution in Germany. |

| Were there any "blots" on the plan? In this regard, the AHG argued that they had accelerated EUR 185 million of the 2029 notes and the court should therefore refuse sanction. | No blots on the plan. It was unnecessary to decide whether the 2029 notes had been accelerated, because acceleration of the notes would not render the plan unlawful or inoperable. |

| Was the company's explanatory statement adequate? | Yes. The explanatory statement did not fail to include sufficient information to enable the plan creditors to make an informal decision. |

| Was it appropriate for the equity to retain their 77.5% shareholding when they were not injecting new money into the group? | Yes. Although Leech J noted that he had the "greatest concern" about the fact that existing shareholders would benefit from the plan if it succeeds, despite providing no support for the plan or any additional funding, it was ultimately held that this was not a reason for declining to sanction the plan. This could, however, be a point of focus in future plans. |

The information provided is not intended to be a comprehensive review of all developments in the law and practice, or to cover all aspects of those referred to.

Readers should take legal advice before applying it to specific issues or transactions.