Supreme Court Confirms Creditors Duty For Directors

05 October 2022

This question has long troubled practitioners and directors (and judges) alike. There have been numerous versions of the test over the years, but the exact point in time when this important duty is triggered, and the precise nature of the duty has, until today, been uncertain.

Today, we have our answer - the Supreme Court delivered its long-awaited judgment in the case of BTI v Sequana [2022] UKSC 25.

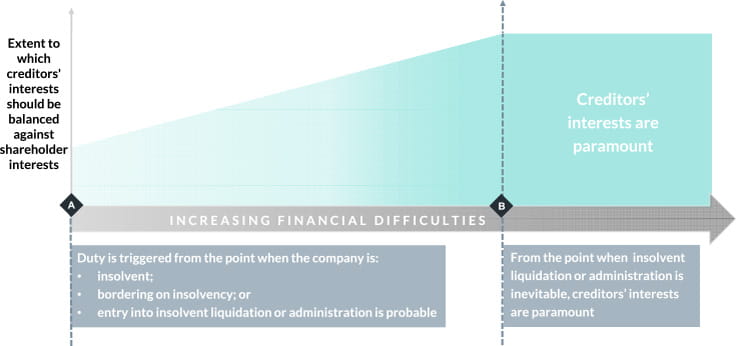

And the answer is that there are two parts to the duty (see also in the diagram below):

| Trigger | Duty |

First trigger (Point A on the diagram): Where the company:

| Directors should consider the interests of creditors, balancing them against the interests of shareholders where they may conflict. The greater the company's financial difficulties, the more the directors should prioritise the interests of creditors. |

Second trigger (Point B on the diagram): The directors know or ought to know that an insolvent liquidation or administration is inevitable (i.e. the same trigger as section 214 Insolvency Act 1986) | Directors must treat the creditors' interests as paramount. |

Directors and advisers alike will be relieved that this decision does not materially change the moment in time when they need to start being concerned about creditors' interests. In the court below, the Court of Appeal framed the duty as being triggered when the directors know or should know that the company is likely to become insolvent, where ‘likely’ means probable. The Supreme Court's test for when the duty is initially triggered is not materially different from the Court of Appeal's test, which is reassuring particularly for any distressed companies considering the duty at the moment. Helpfully, other more esoteric permutations of the trigger for this duty (such as the point when the risk of insolvency is real and not remote) have been put to rest.

That said, the trigger is still not entirely straightforward. "Bordering on insolvency" for example may be difficult to pinpoint in practice. But advisers to directors are likely to stick to the existing practice of taking a fairly prudent approach to the test and respond to creditors' interests at a point in time when the duty might apply.

Aside from the duty trigger, what the Supreme Court judgment also decided (which the Court of Appeal did not do) is how the duty applies after the point at which it is first triggered.

It is now confirmed that the creditors' duty works on a sliding scale basis. Creditors' interests start to become relevant from the point at which the company is insolvent, bordering on insolvency or when administration or liquidation is probable. Thereafter, directors are required to give greater priority to the interests of creditors versus shareholders as the company's financial difficulties increase and the company slides up the scale towards the point where administration or liquidation becomes inevitable (see the diagram).

The judgment runs to 160 pages and there's a lot to unpack, but our first impression is that this is a useful decision which helpfully clarifies the application of the duty but does not materially change the point in time when the duty first applies.

The information provided is not intended to be a comprehensive review of all developments in the law and practice, or to cover all aspects of those referred to.

Readers should take legal advice before applying it to specific issues or transactions.